By David Hoppe

It happened again.

A steel mill spilled another bunch of chemicals into a waterway leading to Lake Michigan. This latest dump made the news on September 8th, a Sunday. It was first noticed the previous Friday afternoon, when, according to a U.S. Steel report, “we detected a light, intermittent oil sheen at one of the outfalls at our Midwest Plant.”

The Indiana Department of Environmental Management, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Park Service and the Coast Guard were “promptly notified.”

This was the second release of something oily into the Burns Ditch waterway by U.S. Steel in three weeks. That makes four chemical spills, including ArcelorMittal’s release of cyanide and ammonia, dating back to August 11.

Once again, Indiana American Water, the company that provides tap water for the community of Ogden Dunes, was forced to shut down its Ogden Dunes treatment facility “until such time as additional data and water testing results confirm there is no threat to the company’s source water at this location.”

“No threat to the company’s source water…” The sad fact of this sorry — and ongoing — episode is that there is always a threat to the company’s source water. That’s because, for generations, that water, better known as Lake Michigan, has been considered an integral part of an industrial process.

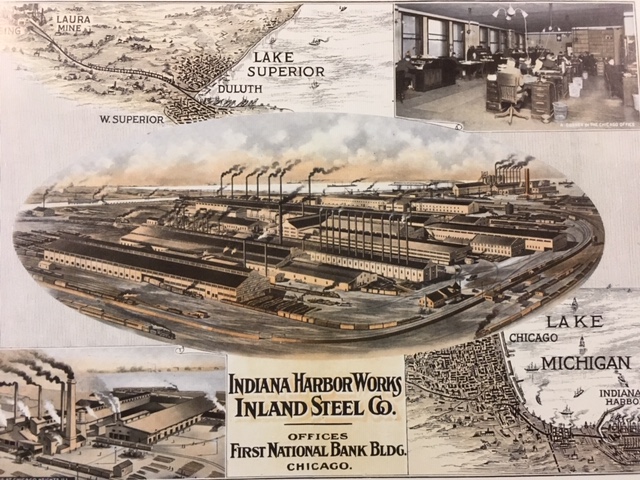

Industrial-scale steelmaking has always been a blisteringly hot, poisonous business, requiring abundant amounts of water. In addition to providing a cheap, seemingly limitless amount of fresh water for this purpose, Lake Michigan was also accessible. Boats loaded with ore from Minnesota’s iron range used to navigate their way from Lake Superior, down to Northwest Indiana, as long as Lake Michigan wasn’t frozen.

In those muscular days, lakes and rivers were considered handmaidens to the country’s industrial ambitions. Factories, mills and power stations were built along the water and towns and cities looked the other way: inland. Water was for dumping and the waterfront sections of communities were often perceived to be mean, dirty and disreputable. It wasn’t until the advent of environmental regulations, in response to egregious pollution, that the waterfronts of many American cities became attractive as residential and recreational destinations.

Given this history, the southern shore of Lake Michigan appears to be stuck at least 50 years behind the times. Although it’s common to hear people talk as though the steel industry here is nothing compared to what it was at the middle of the 20th Century, that’s a relative gripe. The mills still employ thousands; their productivity remains intense.

But the mills’ continuing presence now conflicts with peoples’ growing appreciation for and dependence upon Lake Michigan as a nonindustrial resource. The recent designation of the Indiana Dunes as a National Park is just the latest sign of this accelerating trend.

Ogden Dunes shares a border with the National Park. Earlier this year, when the park designation was finally approved, people living there might have celebrated their good luck, owning property next door to a nationally recognized destination. Now, though, after having their drinking water threatened yet again, they must have their doubts. Do they have more in common with Yellowstone, or Flint?

Throughout this latest sequence of environmental insults, the State of Indiana has played scarecrow, pointing one way, then another, in a feeble attempt to make this conundrum go away. For years the state has treated its northwest corner as a moneymaking afterthought. Although it claims the least amount of coastline on Lake Michigan, its exploitation of that stretch has been historically rapacious and practically ungoverned.

That needs to change. Until it does, the kinds of industrial accidents that have taken place over the past few weeks will happen — and happen again.